The earth-directed coronal mass ejection (CME) associated with the X-class flare of 18 January (STCE newsitem) arrived about 6 hours earlier than expected (STCE newsitem). The impact caused a severe geomagnetic storm (Kp = 9- ; STCE SWx classifications page) late on 19 and on 20 January. Though the storm was not as intense as e.g. the May 2024 storm, many observers commented on the spectacular aurora that were visible, in particular the bright green blobs "dancing" all over the sky. So what was going on?

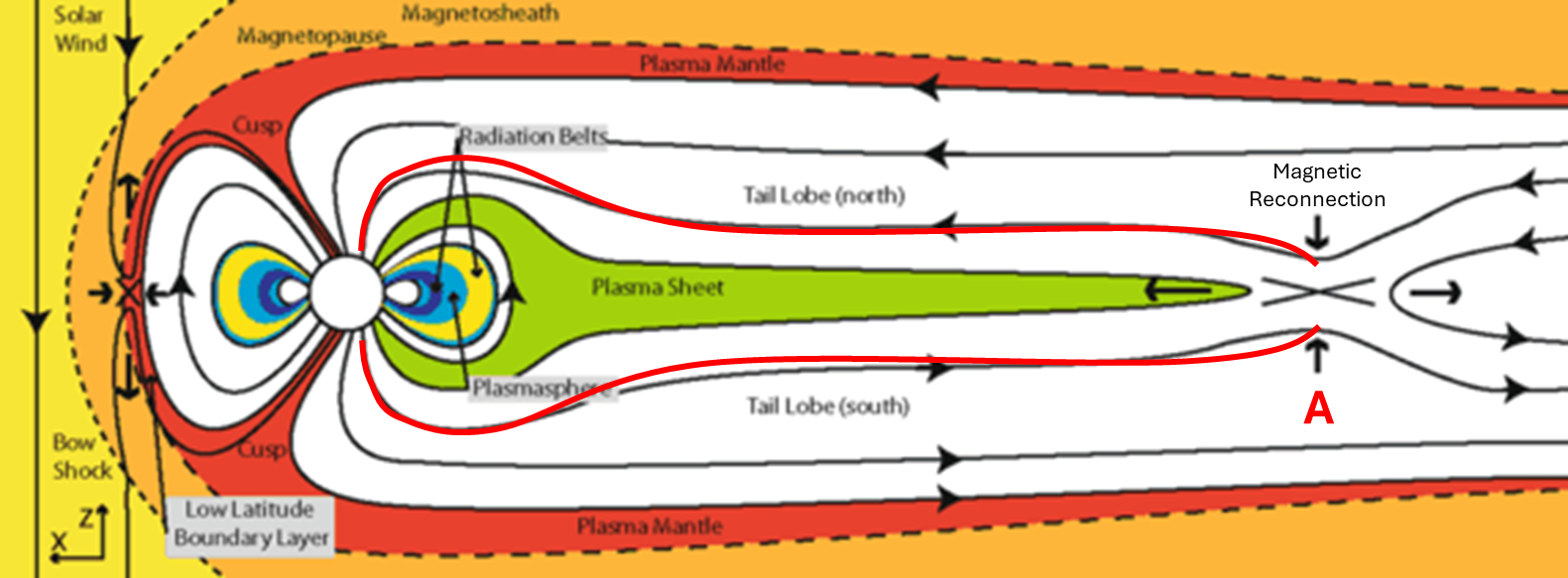

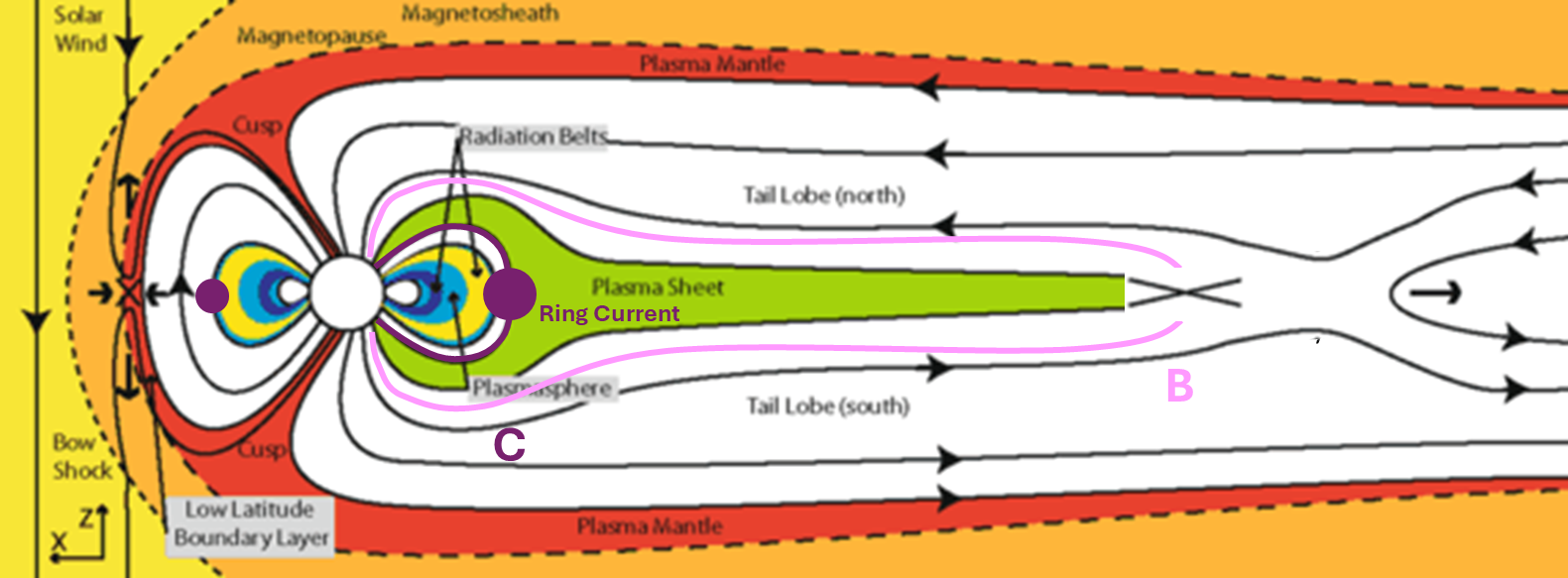

- The Earth is protected by its magnetic field. The solar wind compresses this geomagnetic field on the dayside, and stretches it on the nightside, giving it the shape of a "teardrop" or a "comet". The northern lobe of this magnetotail has its magnetic field lines directed towards the Earth, in the southern lobe the magnetic field lines are directed away from the Earth. This is shown in the annotated sketch (black arrows in Figure 1.A.) underneath, taken from Eastwoord et al. (2014).

- When the magnetic field of the arriving CME has a southward pointing orientation, then a good connection with the geomagnetic field (dayside) is possible. As a result, the magnetotail (nightside) gets compressed by the passing CME. This pushes the two lobes of the magnetotail closer together. But as their magnetic field lines have an opposite direction, a "short-circuit" (magnetic reconnection) takes place, accelerating the particles (mostly electrons) violently to Earth. Under normal solar wind conditions, this magnetic reconnection occurs at distances in the range of 23 to 31 earth radii (Nagai et al. 2023).

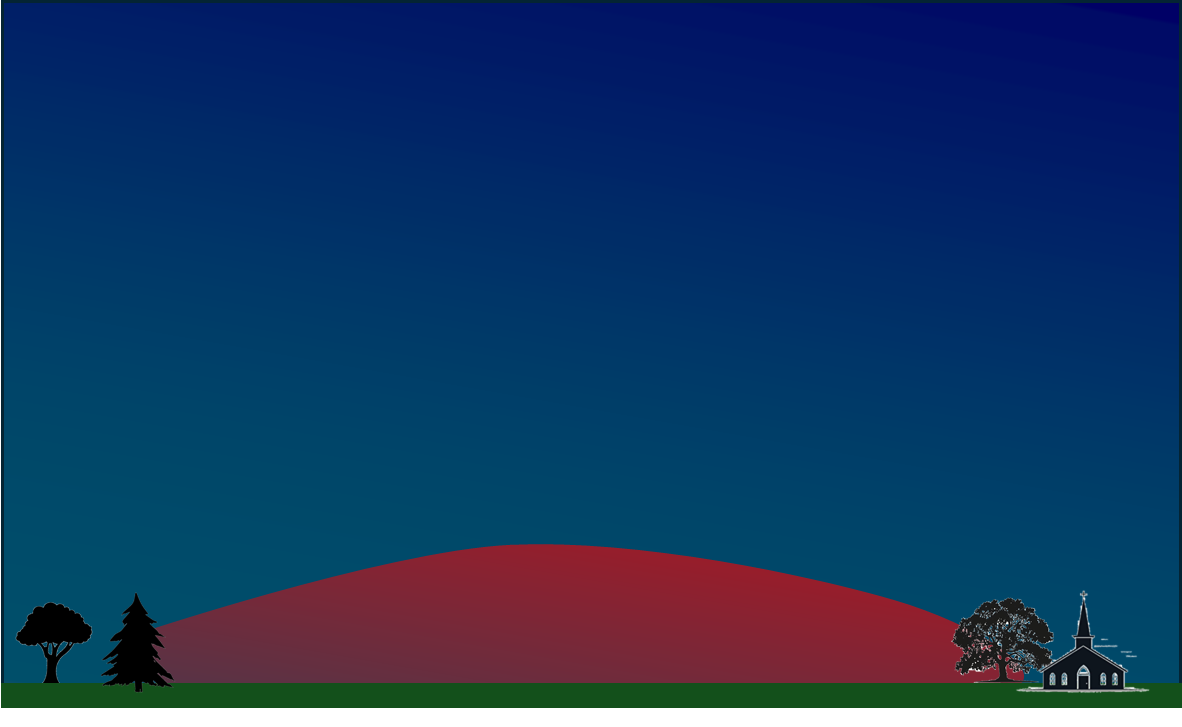

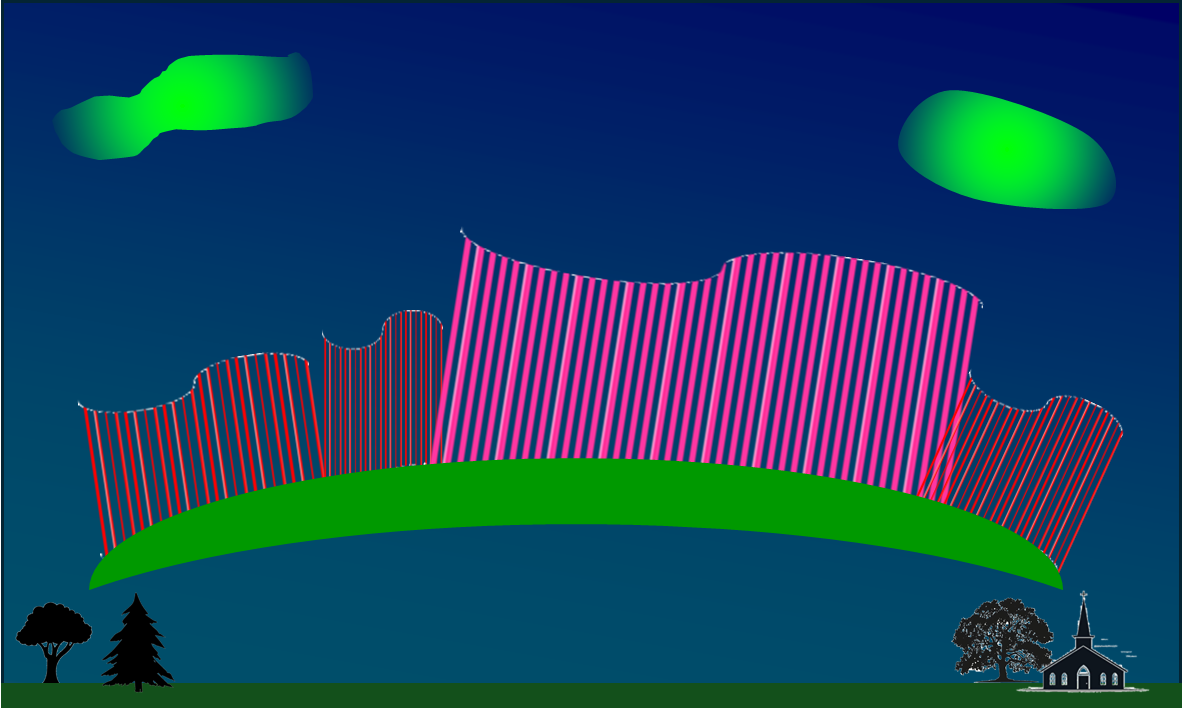

- The magnetic field lines guide the released particles towards the Earth's latitudes and locations where the aurora and the auroral oval are typically seen. The typical green colours are caused by collisions with oxygen at an altitude between 100 and 200 km, while the rarer red aurora (requires strong storms) are caused by collisions with oxygen at higher altitudes between 200 and 400 km (BIRA-IASB). This is why for Belgium and other mid-latitude locations, one usually sees red aurora because they are the highest in the sky and thus visible from further away (from the polar regions that is). But even then, for Belgium, a strong geomagnetic storm (Kp = 7) is already required to catch a glimpse of these reddish aurora low above the northern horizon, as shown in the sketch of Figure 2.A.

Figure 1.A.

Figure 2.A.

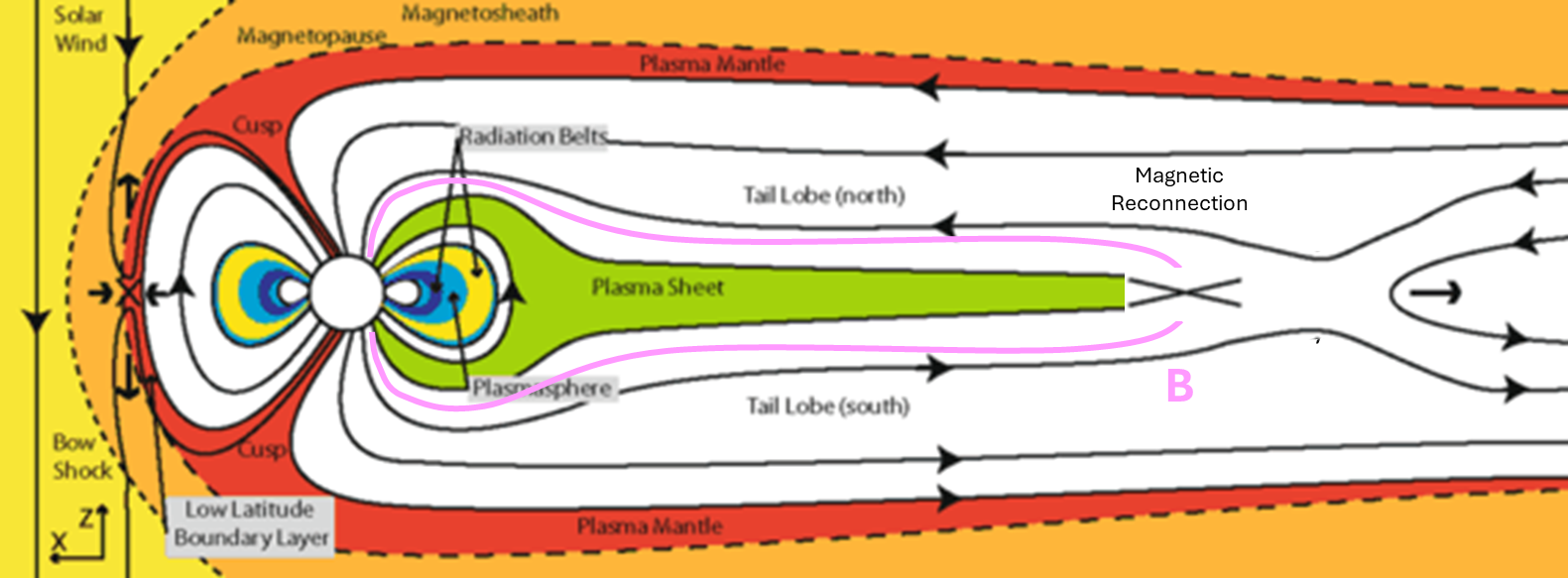

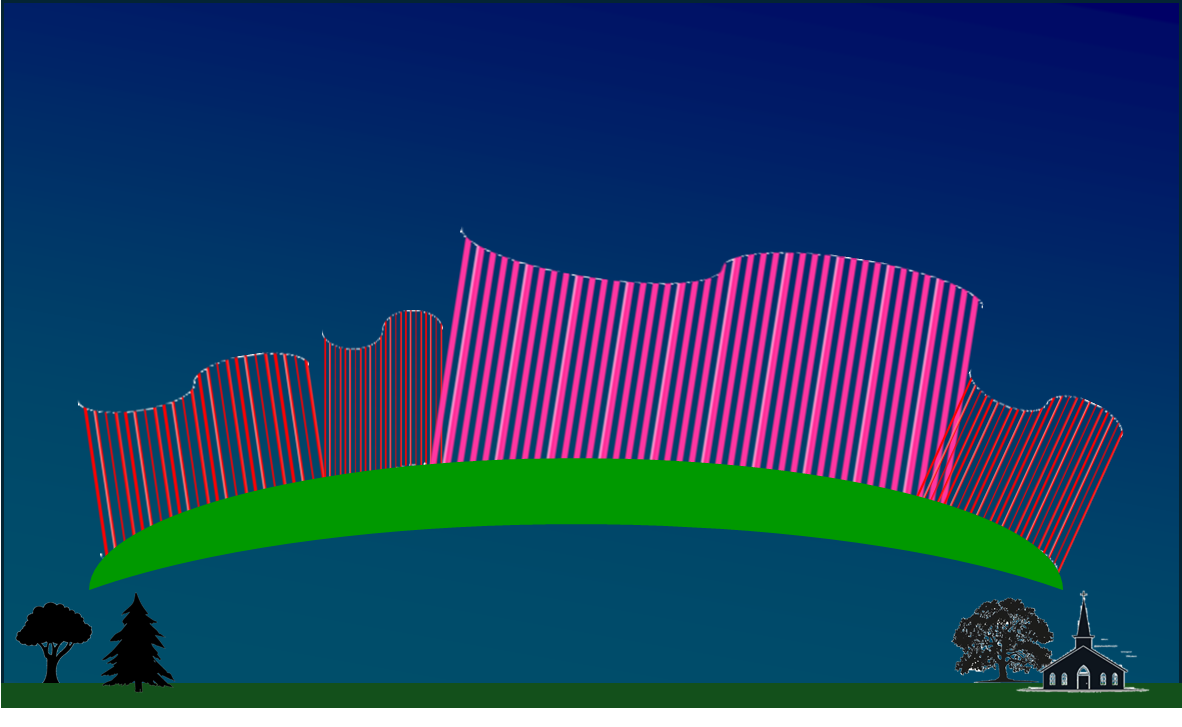

Things become more interesting when the southward pointing magnetic field of the CME is very strong or remains southward for several consecutive hours. This results in a severe or extremely severe geomagnetic storm, with Kp respectively reaching 8 or 9. The stronger the field and the longer-lasting the southward orientation, the stronger the resulting geomagnetic storm will be. Typical examples are the October 2024 (Kp 9-) and the May 2024 (Kp 9o) geomagnetic storm. Now, in this scenario, the magnetotail gets much more compressed, and the magnetic reconnection can occur much closer to Earth at distances of 20 earth radii or less (Nagai et al. 2023) as shown in Figure 1.B. That change in location makes a difference, because the connecting magnetic field lines now guide the released particles towards Earth's mid-latitudes and occasionally even further equatorwards. This means that the aurora, as seen from Belgium, are now getting higher in the sky, with increasing chances that also the low-altitude green aurora become visible, as shown in Figure 2.B. Also, because the magnetic reconnection in the magnetotail is taking place over a much wider area, the auroral oval becomes wider.

Figure 1.B.

Figure 2.B.

So where were those bright green blobs coming from during last week's storm? Those were clearly outside the location of the typical red and green aurora, appearing all the way up into the zenith and even a bit further southward as seen from Belgium. Well, the source of these aurora is not located in the magnetotail, but in the ring current. The ring current is an electric current encircling the Earth at geocentric distances between 3 to 8 earth radii (nightside) in the equatorial plane, partially overlapping with the outer radiation belt, as shown in the sketch of Figure 1.C. So, the ring current is even closer to the Earth than the locations of the magnetic reconnection of the "normal" aurora. During a particular strong geomagnetic storm, it may happen that interactions between the magnetic waves and the protons present in the ring current, move those protons out of the ring current such that they move along the magnetic field lines to locations even further equatorward than the typical aurora (see also Xiao et al. 2014). There, these runaway protons collide with particles from the upper atmosphere and cause those pulsating green blobs, called "proton aurora". Appearing much higher in the sky than the usual aurora (Figure 2.C.), these green patches brighten and fade in a matter of tens of seconds.

Figure 1.C.

Figure 2.C.

The images underneath show the aurora from last week's geomagnetic storm, as observed from Brussels on 19 January between 21:30 and 22:15 UTC. The top figure shows the typical aurora as seen due north. Compared to the May 2024 storm, the main differences were that the aurora were not as high in the sky this time, and the reddish hues were a bit less pronounced than almost 2 years ago. The two smaller pictures in the bottom row show 2 examples of proton aurora, the lower left in the due east direction and the lower right picture as seen near the zenith (directly overhead). Barely a few pictures could be taken of each blob, that's how fast they appeared then faded away. Many observers commented on the "disco-like" feeling they got while observing these dynamic, pulsating green features often as bright as the full moon. On social media, there are plenty of really good and astonishing images and clips of the phenomenon. Examples are Jonas Piontek, Wil Photography, and Anthony Bongiovanni. Fiona Lee and Kelly Kizer Whitt provided examples of proton aurora observed during the 11-12 November 2025 storm.